How We Find Our People

Who are your people?

We ask that question casually—at parties, in new jobs, or when we move to a new city. But underneath it is something deeper: we’re all looking for connection. Belonging. A sense of who we are and where we fit.

For most of history, “our people” were just… our people. Family. Clan. Tribe. Language group. Religious community. Our identities were often handed to us at birth and expected to remain mostly fixed. Where you were born, what language you spoke, even what foods you ate told others who you were.

But something is changing.

Thanks to global migration, the internet, urban life, and evolving social norms, our identities have become more fluid. We move across borders. We join digital communities. We find belonging in fan groups, fitness classes, coworking spaces, and book clubs. We assemble tribes—not by blood or birthplace—but by affinity and shared experience.

In sociology and anthropology, we’re seeing a shift from “deterministic” views of identity (you are what your birth group says you are) to “constructivist” ones (you are who you grow, choose, and connect with). And while that might sound academic, it’s happening all around us, every day.

A gamer in Nairobi might feel more connected to a player in São Paulo than to the people on her street. A tattooed barista in Portland might feel more understood at a comic convention than in his family’s church. A young entrepreneur in Mexico City might be part of multiple overlapping networks—none of which are defined by language or ethnicity alone.

This isn’t just interesting; it’s important. The way we group ourselves shapes how we see the world—and how the world sees us. It influences what ideas we’re open to, who we trust, and even how we imagine change.

For people of faith like me, this shift invites both curiosity and reflection. If our calling is to love our neighbors, we need to be better at seeing who our neighbors actually are—and how they see themselves.

Belonging is still essential. But the ways we find it have changed.

So ask yourself:

Who are your people?

Who do you trust?

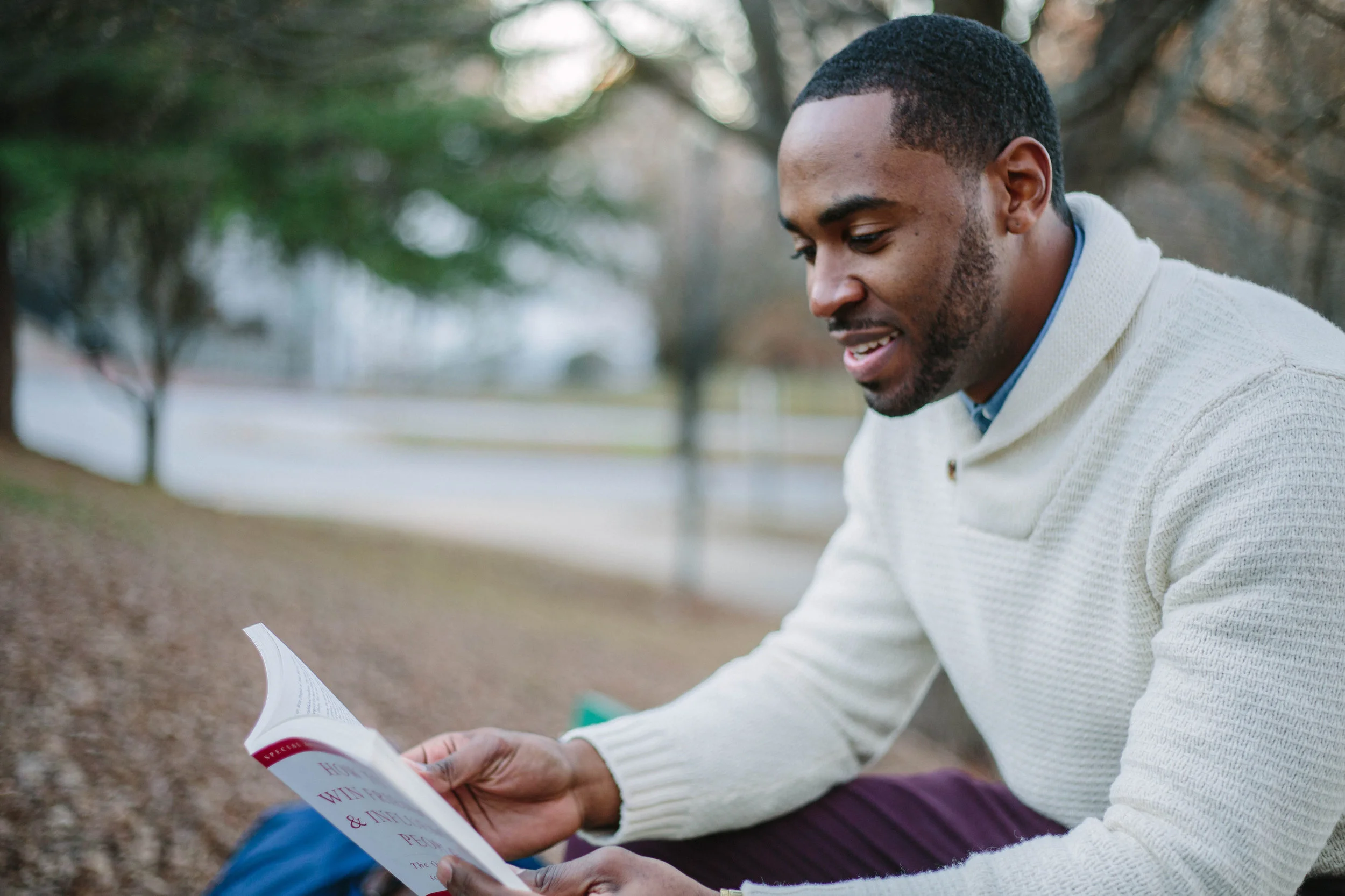

Who do you influence—and who influences you?

I’m exploring these questions more deeply: how we form social groups, how ideas spread between them, and what it means to live meaningfully in a world where identity is no longer static.

Wherever you are, whatever circles you run in—you’re invited.

On Fandoms

For many individuals, especially within increasingly fragmented and digital societies, fandoms provide something that traditional institutions often no longer offer: a meaningful and supportive community.

In lecture halls and living rooms alike, on social media platforms and at bustling comic cons, one thing becomes unmistakably clear: fandoms are truly everywhere. Whether it’s the widely recognized geek culture mainstays such as Star Wars, Marvel, Harry Potter, and anime, or more niche hobbyist communities like dedicated fly fishermen, passionate tiki culture aficionados, or classic car enthusiasts, millions of people around the globe dedicate substantial amounts of their time, money, creativity, and emotional energy into engaging with fictional worlds, beloved characters, intricate lores, and distinctive aesthetics. As an anthropologist, I find myself deeply fascinated by what this widespread phenomenon says about human beings—and more importantly, by what it might reveal about our most fundamental desires and deepest longings.

Fandoms as Modern Tribes

Fandoms function much like tribes in contemporary society. They offer identity, a strong sense of belonging, a shared language, established rituals, and even sacred texts—such as extended universe novels or detailed liner notes. For many individuals, especially within increasingly fragmented and digital societies, fandoms provide something that traditional institutions often no longer offer: a meaningful and supportive community. This sense of connection helps members navigate the complexities of modern life while fostering a collective cultural experience.

Humans are inherently meaning-makers. We gravitate toward stories that help us interpret our lives. Theologically, this resonates with the idea that we are created in the image of a relational, narrative God. In fandoms, people rehearse stories of heroism, sacrifice, transformation, and redemption—stories that often echo biblical patterns even when they aren’t intentionally Christian.

Ritual and Devotion

Fan practices—such as cosplay, writing fan fiction, organizing watch parties, and collecting memorabilia—may initially appear trivial or merely recreational, but they closely mirror many aspects of religious behaviors. These activities are deeply embodied and communal experiences that often involve significant personal transformation. For instance, a fan dressing up as their favorite character engages in a ritualistic act that parallels how a believer participates in religious ceremonies, both fostering a powerful sense of connection to a larger narrative and a shared community.

This doesn’t mean fandoms are religions, but it does mean they meet some of the same human needs that religion addresses: the desire to belong, to find purpose, to encounter wonder. Through an anthropological lens, this isn’t something to mock or fear—it’s something to understand.

Longing for Transcendence

Underneath the memes and merchandise lies a deeper hunger. Fandoms reflect the human desire for transcendence—for a story bigger than ourselves, for heroes worth following, for worlds where justice is real and evil is overcome. These are theological longings.

C.S. Lewis once said: “our lifelong nostalgia… is the truest index of our real situation.”[1] Fandoms are a kind of cultural nostalgia—echoes of Eden and signposts pointing us to a story that is actually true. Christians believe that story is the gospel: the tale of a hero who sacrifices himself to save the world, who defeats death, and who invites others into his victory.

Engaging Fandoms with Curiosity and Compassion

Rather than dismissing fandoms as escapist or childish, people of faith can approach them with curiosity. What does this fan love? What does this story say about the world and what it means to be human? These questions open doors to meaningful conversations, not just about pop culture but about purpose.

Faith invites us to see culture not as a battleground to win or a swamp to avoid, but as a field ripe for observation, understanding, and ultimately redemption. Fandoms aren’t distractions from the real world; they’re windows into how real people search for meaning, beauty, and connection.

A New Frontier

Fandoms remind us that humans are storied creatures. We were made for worship, for wonder, for belonging. Whether it’s through scripture or Star Trek, humans are constantly trying to locate ourselves in a bigger narrative. I see fandoms not as competition to my faith, but as cultural evidence that people are still yearning for it—even if they don’t know it yet.

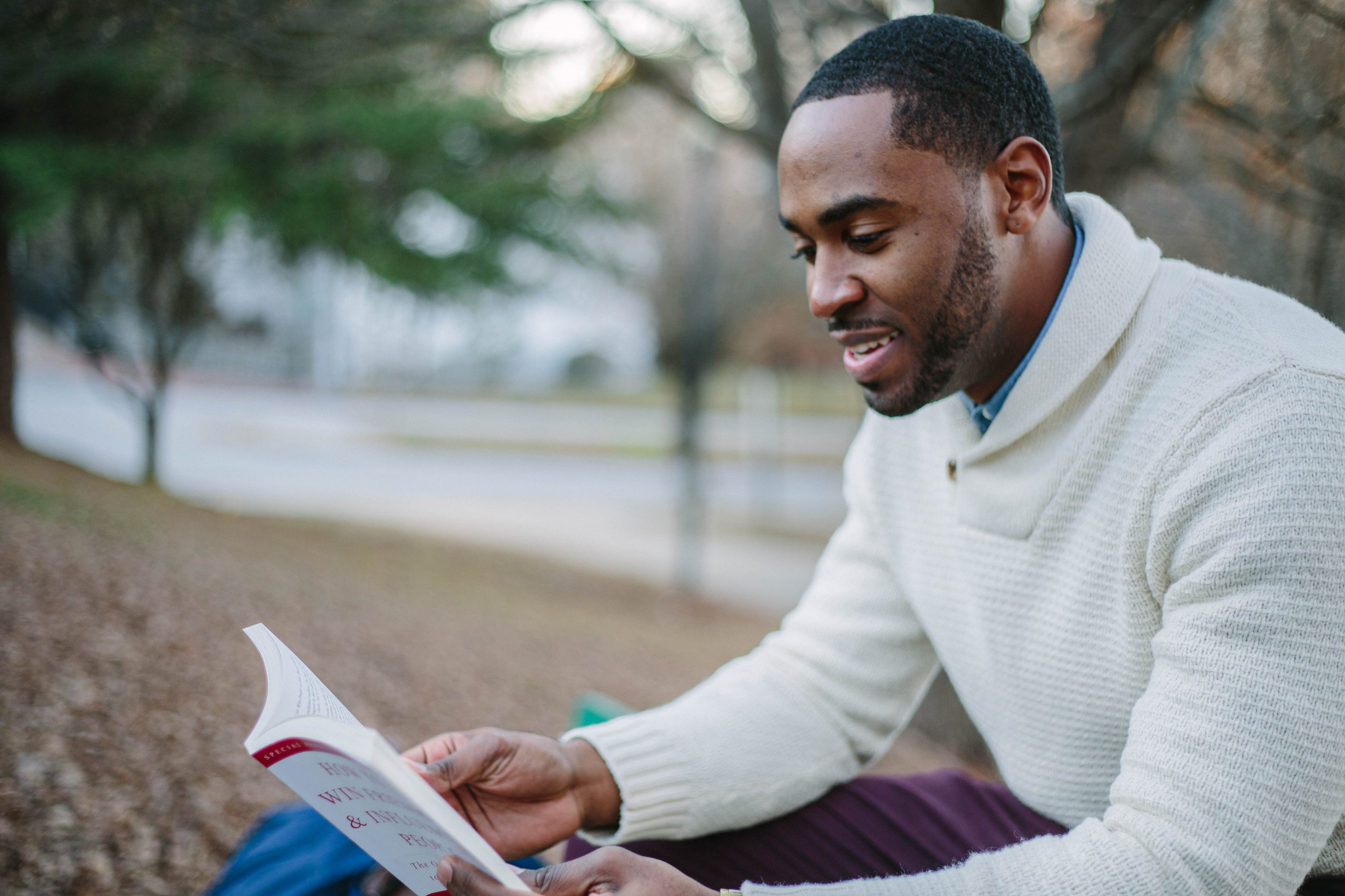

On Being A Stranger

You look around and see things you recognize– commuters on their way to work, construction in the streets, shop clerks opening for business. All typical stuff, but none of it feels familiar. You’re not sure how you fit in. You’ve lost all confidence that you know the rules for how to act or what to say. You feel out of place- conspicuous, yet totally inconsequential to the place you find yourself in.

Welcome to being a stranger. Anyone who’s ever lived in a foreign country has felt this feeling, but sometimes the sensation doesn’t even require that you travel abroad. The upper-middle class guy who has to go downtown for a meeting might get a brief taste of it. The woman in an all-male office environment. The child who is briefly separated from Mom in the department store. This is what it feels like to be a stranger, and it’s how God’s people are meant to live on this earth.

Throughout the Bible, we regularly see God’s people being uprooted from any home they try to establish and scattered into other lands to live among other peoples. This continues to this day; we are not supposed to be at home here.

It’s okay to long for “home.” But that longing for a place to call our own should drive us to pursue God all the more. The Bible reveals to us what “home” will be like, and that knowledge should make even the best this world has to offer us lose its appeal. We’re strangers, saved to a new kingdom. Here, we’re just passing through.

Look for signs that the people in your church are becoming too comfortable in the cultures in which they find themselves:

Get super angry/offended over political debates: We are to avoid foolish debates and disputes about the law, for they are unprofitable and worthless.

Isolation/fear/hatred of foreigners: We should have compassion for those who do not know Christ, and we should have more in common with believers from other lands than we do with non-believers in our own land.

Orienting life around products of culture (sports, stories, idols, identities): Christ alone is worthy of our worship, and we must not find our identity in anything but Christ.

Social status/concern with what people think: We do not fear men, but God. We are not ashamed of His gospel.

If you observe these things in people who claim to be followers of Christ, they’ve likely lost sight of the fact that this world is not their home. They need to be reminded that we belong on the margins– unaccepted, uncomfortable, and disenfranchised.

The remedy? Point them to the One to whom we belong. Remind them of the kingdom of our citizenship. This world as we know it will pass away, but God’s kingdom will reign forever. As long as we’re here on this earth, we are strangers. Strangers don’t get tangled up in the affairs of this world.

Fleeing The "Values Gap"

About a month ago, I came across this Tweet from Andrew Walker, Senior Fellow at The Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission and Professor of Ethics at the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary:

In just a few months, I’ve met three Christian families who said they’ve fled California for Middle Tennessee because of how hostile and parasitic the culture was to their faith and values. It’s hard to overstate just how serious the values gap is widening and impacting America.

— Andrew T. Walker (@andrewtwalk) June 24, 2019

I cannot stop thinking about the idea that Christian families would move from California to Middle Tennessee in order to “flee” the “values gap.” I can’t fathom someone leaving California simply because of the culture there. The very notion of this is offensive, frustrating, and disheartening.

I’ll admit my initial response was to be offended. Not so much for myself, but for thousands of my IMB colleagues who willingly leave the comforts of home to move their families to faraway places often to be the only Christian witness among entire cities and people groups. In obedience to Christ’s commission, these people live in places that are truly difficult; they face actual persecution and routinely live with:

Hostile governments that make it illegal for Christians to share their faith

Local laws the limit freedom of assembly in order to persecute churches

Officials listening to their phone calls (and arrest any nationals who talk to them)

Severe weather, high temperatures with no A/C

No medicine or healthcare within a day’s reach

Random arrest and detention, often deportation

These are the daily realities for so many overseas workers. Why do they put up with these things? Because Jesus is worthy of the worship of all people, and so many still do not know him. They endure these things in order to make disciples because that’s the mission of God’s Church. How dare we offer our support for them to suffer hardships over there when we’re not willing to endure discomfort here?

I also take offense on behalf of my Christian friends and family in California (I was born and raised there) who have faithful, fruitful ministries there. Sure the traffic is terrible, the cost of living is high, and politics are liberal. Sin is celebrated, idolatry is rampant, and tolerance is selective. But many of “the nations” we read about in Scripture live in California! Lots of the crazy agendas found there are people struggling to make sense of the world; if we enter that struggle with them, we can offer Jesus as a viable alternative to human philosophies and schemes. The opportunity to make disciples is tremendous! Surely someone might brave the delicious fresh food, freedom of expression, and year-round sunny, 75º weather to be salt and light in a place that desperately needs it!

My offense soon gave way to frustration. I wanted to find these “California Refugees” and figure out what in the world they were thinking. How could you adopt such a consumeristic approach to life–literally shopping for a place that makes you more comfortable? Why would you expect (or even desire) to live in a place where the majority shares your values?

And, by the way, what values are we talking about here? Comfort? Safety? Christianized subculture? These are not Kingdom values! We’ve been sent like lambs among wolves! Jesus literally warned us that the world will hate us if we follow Him. Of course the nonbelievers around us don’t value the things we value– they are hopelessly dead in their sin. And how will they know that God has made a way unless someone tells them? Who will tell them if we all move to Nashville?

My frustration is not with the fact that Christians would move, but with the criteria they’re using to make these decisions. There a lots of good and valid reasons to leave California–financial challenges, changes to employment, family emergencies, etc. But leaving because the “culture is hostile and parasitic” an adventure in missing the point of why we’re left on this earth rather than being whisked away to heaven upon our salvation.

And where can we go to flee the “values gap?” Middle Tennessee (the beautiful part of the country that gave us the Grand Ole Opry and hot chicken) may have the veneer of “Christianity,” but by moving there, you’re really just exchanging California’s immoral sexual ethics and support of abortion for Nashville’s materialism, racism, and greed. No place is “safe”–and that’s sort of the point.

This Tweet left me disheartened. I’m saddened that Christianity in America could look like this. The desire to isolate ourselves from the world is probably natural. But for God’s people, this sort of dereliction of duty is a discipleship and discipline issue.

Can you imagine what we’d say about a missionary to South Asia who wanted to leave because the people in his community didn’t share his faith and values? What if he wanted to relocate because of the culture gap? We’d say he was being ridiculous and a bad missionary. We’d ask him what he thought he was getting himself into in the first place. So it is with God’s people who are dismayed by the challenges of being the minority in society–in Christ we are necessarily outsiders in this world.

Thankfully, more and more men, women, and children are taking seriously their role in God’s mission. They’re looking for opportunities to deliberately interject themselves into communities who need to know that God loves them. I continue to be encouraged by stories of regular Christians who are holding loosely to their preferences in order to follow Jesus into the “values gap” and plant their lives there for God’s glory.

We Don't Make The Rules

In order to prepare for life and ministry in the Middle East, a young missionary once devoted several years to the study of Islam. He read the Qur’an, visited several mosques, interviewed an imam, and even took introductory courses in Arabic. He prepared an entire apologetic based on what he had learned to be common Islamic objections to Christianity. He found various contradictions in Muslim thinking that he intended to exploit as soon as he had the opportunity to engage in evangelism of Muslim people.

This missionary had done his homework, yet when I connected with him about six months after he had arrived in country, he we extremely frustrated. Everywhere he went, he found people who claimed to be good Muslims, but none of them believed exactly what the missionary had learned that Muslims believed! Undeterred, the missionary had found himself in the awkward position of teaching Muslims what they were supposed to believe, just so he could then explain how Jesus was better. He went around rebuking nominal Muslims for not following the tenets of their faith. He debated religious leaders over what it really meant to follow the teachings of the prophet Muhammad. How was he to have a fruitful conversation with these people, if they were so ignorant of the religion the claimed to follow?

It seems silly, doesn’t it? Why would a Christian missionary, sent to make disciples of Jesus, waste any time at all explaining the teachings of the Qur’an instead of teaching the Word of God? May God save us from thinking that we have so figured out the people with whom we’re interacting that we fail to even listen to what they’re actually saying.

Lately my Twitter feed has been buzzing with debates: Christians debating non-Christians about the science of fetal heartbeats, Christians debating other Christians about the merits of Critical Race Theory as an analytical tool for understanding human experiences. Conservatives debating liberals over socialism. In every case, I get the strong impression that despite all the back-and-forth, very little communication is happening. The worst part about it all? Christians–God’s people who have been sent as His ambassadors, witnesses, and disciple makers–insisting that they are the keepers of the “rules” of the discussion.

The thing is, philosophies and perspectives don’t always fall neatly into well-defined categories. Recent studies indicate a resurgence of socialism in U.S. politics. Conservatives have been quick to dismiss these would-be socialists with cautionary tales of the failed social, political, and economic policies of Colombia or the Soviet Union. But are young Americans really advocating for a government takeover of all businesses, transportation, banks, schools, farms, and factories? If we stop and listen long enough to get past the word “socialism” and it’s historical definition, we might find that they’re using the word quite differently than the Viet Cong might have in the 1950s and 60s. In reaction to unchecked economic competition, some are looking for alternative systems. Their reasons are valid: spiraling debt, skyrocketing insurance premiums, low-paying jobs, and burdensome tax laws are all heavy burdens to bear. Jesus had much to say about worry, generosity, dependence on God to provide our needs, caring for widows, orphans, and foreigners, and working hard, and good stewardship. If Christians were to engage with “socialists” around these issues, around the challenges we all face every day, the likelihood of us having solid opportunities to share the gospel only increases.

Isn’t that our goal? More gospel proclamation and more disciple making? Are we out to convert people to Christ, or to capitalism? If we shoot holes in the logic of their patchwork-quilt of a worldview, are they any closer to Jesus?

It must be said that in our segmented society, all communication is essentially cross-cultural. Even when we talk to people who seem to be a lot like us, we must overcome a variety of cultural and sub-cultural barriers if we’re going to understand and be understood. God’s people on mission should pursue dialog, not diatribe. Let’s not become experts in economics, philosophy, or religion in order to demonstrate our mastery of academic concepts, let’s be experts in Christ and Him crucified, that more would know Him.

The reality is that we don’t get to set the rules. Those to whom we’ve been sent can change the definitions of words, hold contradictory opinions, change the standard, lie, deny, and ignore. We will never be able to keep up with their philosophies, trends, political ideologies, and social constructs. But that’s okay. We can be experts in Jesus, and He is what people need after all.

Knowing, Being, Doing

My job is to design training for cross-cultural workers. It’s really interesting work. First, we determine what a good and healthy worker needs to know, be, or do. Along the way, we’ve compiled quite a list of knowledge, character traits, and skills that faithful and effective cross-cultural disciple making requires. Some things on the list are exactly what you might expect: missionaries need to now how to share their faith, interpret scripture, and learn new languages and cultures.

Missionary knowledge is (relatively) easy. It’s easy to assess what a Learner already knows-just ask her a series of questions. Where there’s a deficit in understanding, it’s easy to provide her with the needed information. Retention of that information, then, can be checked over time through simple quizzes.

Missionary skills are a bit more difficult, because a skill is learned over time through practice. Skills have to be developed. Nevertheless, it’s pretty easy to assess a missionary’s skill: have an expert observe the worker’s behavior, and that expert can quickly get a sense of his or her skill level.

Missionary character is clearly the most difficult to assess for, train to, and evaluate. Of course, behavior is the primary indicator of what’s inside a person, so we can begin to understand who a person is by watching what they do. But being a missionary–especially a good one–is more than just activity; in many ways, there’s a particular missionary perspective that makes all the difference in a person’s usefulness to cross-cultural disciple making.

No one is born a good cross-cultural worker. Becoming a good missionary is a matter of discipleship- learning, practicing, improving. But the result of training is understanding, a Christlike attitude, and lots of transferrable skills. Would that every Christian received this sort of training!

Diplomatic Immunity

Regardless of your take on whether or not all Christians are "missionaries," (see my previous post to read why I say we are, in fact, all missionaries), the scriptures are clear that all of God's people have a place on His mission. So it would make sense, then, for us to stop every once in a while to reflect on whether we are doing mission well. If we are ambassadors of God's kingdom here on earth, our lives should look, well, ambassadorial. Right?

An ambassador doesn't live according to his own agenda. He lives as a messenger of the one who sent him. In some ways, that makes the ambassador a dignitary. His status as official representative gives him an importance that exceeds his own. This is why countries allow diplomatic immunity from local laws.

As Christians, we enjoy a certain amount of diplomatic immunity in this world. Because we represent the King, we're held to a different standard than everyone else. We're above the human tendency to repay evil for evil. We're no longer slaves to sin. Karma doesn't apply to us. We're free from worry, doubt, and fear.

Yet even the privileged ambassador knows he is only a stand-in. At the end of the day, our King has a limitless number of representatives. We're special, but only because he chose us. Beyond that, we're the same (or worse) than everyone else. Because we know this truth (and constantly remind one another of it), we can't think too highly of ourselves. So we humbly speak the truth in love. We're careful to differentiate between our opinions and the very word of the King who sent us. And we commit to studying His decrees, lest we dishonor our King by speaking out of turn.

We have been sent by God to be His people among the nations of the earth. We must live in such a way that when the world looks at our lives, they see examples of what life in Christ looks like. They see less of us, and more of Him who sent us. This is what it means to be on mission.

Who Are You Calling A Missionary?

I recently has the pleasure of participating in The Mission Table, a conversation with mission leaders about some key aspects of the church's role in God's mission. Be sure to check out the video.

The topic we discussed in this episode was, "Are all Christians Missionaries?" I say yes. I'm in good company, as Charles Spurgeon famously said, "Every Christian is either a missionary or an imposter." That's a pretty bold statement, and it's one that has become unpopular over the last few years. Unfortunately, the arguments against using the idea that all of God's people are missionaries seem to be based more on tradition than scripture. Let's look at common arguments for the distinction:

"If you apply the word to everyone, then you minimize the work of those who go to faraway places to share the gospel with people who have never heard."

This isn't necessarily true. Many in the missions world look for ways to prioritize the sending of people to proclaim the gospel to those people who have not heard it. I'm one of those people, and the way we honor those who serve in difficult places isn't by reserving the word "missionary" for them, but by financially supporting them. This is what Paul was referring to in 1 Corinthians 9:1-18, when he pushes back on the Corinthian church for being stingy in supporting his work.

"To be a missionary, you've got to be crossing cultures."

Of course mission entails crossing cultural barriers with the gospel. But how distant does the culture need to be before it's considered mission? As God's people we are necessarily outsiders. We've been called out only to be sent back in, just as God sent the Son. Our citizenship is in a heavenly kingdom, and we're not from around here anymore. As sent-ones, we live in the tension of taking the universal, unchanging gospel and translating it into the dynamic, sin-filled cultures in which we live. This is the mission of God's people, and it requires us to cross those cultural barriers in order to make disciples. For some of us, that means moving across the world to live among those who have never heard the gospel. For others of us, it means overcoming more familiar barriers to the gospel. Either way, the work is the same.

"Not everyone has the Apostolic (Missionary) Gift."

It is true, of course, that not all Christians are gifted as apostles. But neither to all Christians have the gift of evangelism. Does that mean that we're off the hook when it comes to evangelism? Certainly not! We must take care not to conflate the missionary gifting with the missionary identity of all who are in Christ.

"If everything is a mission, then nothing is/If everyone is a missionary, then no one is."

I'm with missiologist Christopher Wright, who says he hates this old knock-down. If everyone is a missionary, everyone is a missionary. A missionary is "one who has been sent on a mission." Who among us hasn't been sent? Nobody uses the same argument about being salt and light, or about being witnesses. Nobody says, "If we're all witnesses, then none of us are." Is everything a Christian does worship? It should be. Are we all ambassadors? Salt? Light?

"People do all sorts of things in the name of mission."

Let's be clear: all Christians are missionaries, but not all Christians are good missionaries. Much of what is happening in churches in the U.S. is very bad mission indeed. Some of this has to do with millions of American Christians being told that they aren't missionaries (so why should they be expected to act like they are?). The only way to get all of God's people in a consistent posture of gospel proclamation across cultural barriers is to call them back to their sentness.

Despite the well-intentioned efforts of those in the missions world to further narrow the definition of missionary, Christians around the world are realizing that their purpose on this earth is to join God in his redemptive mission. Consider the missional movement of the last fifteen years: God's people, recognizing that something has been missing from their obedience to Christ, rediscover what it means to be on mission. But as they explored the implications of their sentness, the only help they received from the international missions world? "You're not missionaries."

Without the benefit of input from those they had sent out to "the nations," church leaders were left to their own devices in redeveloping their missiology. Using their Bibles and their understanding of culture, missional Christians in the West came to the conclusion that a missionary isn't "someone with apostolic gifting," it's "someone sent on a mission." This applies to all of God's people.

We are all peers in God's mission. We must work in unity in order to be faithful to the Great Commission. This means tearing down the artificial walls between "mission" and "not mission" and calling all Christians everywhere back to their missionary identity in Christ.

You Have Been Sent

I had the pleasure of speaking in chapel at Shorter University about "Living As Sent People," from Romans 16. The human history content is based on teachings from a mentor of mine, Thom Wolf.

Outsiders

When everyone around you looks, dresses, talks, eats, and shops like you, you feel like an insider. I grew up in the suburbs of San Francisco, and we lived in a sort of culture bubble. Though our city was ethnically diverse, it was culturally homogeneous. I'm a bit ashamed to admit it, but it wasn't until I was 17 years old that I ever truly felt like an outsider.

The summer after my Senior year in high school, I worked at an urban mission center in San Francisco. For three months, I lived in the parsonage apartment of a small Baptist church in a particularly rough part of the city. I was surrounded by Asian immigrants, Hispanic migrants, and low-income black people. For the most part, people were friendly and accepting, but I remember feeling so... different.

When you're an outsider, you behave differently. You keep your guard up. You don't assume you understand what's going on, what people are thinking. You have to work a bit harder to understand and to be understood. You quickly learn to find someone on the inside to help you navigate it all.

We Christians tend to do better when we're in the minority. Our rightful place in this world is as outsiders. After all, we are "called-out-ones" (ekklesia). When we're outsiders, we study culture, rather than consume it. We recognize the significance of cultural barriers and we're pressed to rely on God to overcome them.

If you've not spent a good deal of time as an outsider, I encourage you to intentionally put yourself in that position. Explore a new neighborhood. Visit a cultural center. Attend an ethnic festival. Eat strange food. This is the best way to re-orient your perspective on your relationship to the world around you.

Until we recognize that in Christ, we are necessarily outsiders, we really cannot know what it means to be sent into the world on God's global mission. Our citizenship is of a heavenly kingdom, and we've been sent here as God's ambassadors.

Bad Missionaries

If you're a Christian, you have a mission.

Your mission fits into God's broader mission, which is to glorify Himself by redeeming all of creation. Our part is to make disciples by proclaiming the gospel of Jesus in word and deed among all people.

A missionary is someone on mission. I know there are some who prefer to reserve the word only for certain people with certain gifting serving in certain ways, but this isn't helpful because it indirectly communicates that some of God's people don't have a mission; as if God were pleased with a class of Christians who sit on the sidelines. When it comes to mission, there are no spectators. No matter how much you read your Bible, pray, worship, fellowship, and give, you cannot follow Jesus and not go.

"As the Father has sent Me, I also send you." –John 20:21

Of course, God doesn't want all Christians to pack up and move to Myanmar. Some, He will lead to faraway places to minister among people who seem to be very different from us. Others will be lead to live and proclaim the gospel in their hometowns. Regardless of location, the activity is the same: we obey God's word, study culture, translate the gospel into that culture, and make disciples.

"Therefore, we are ambassadors for Christ, certain that God is appealing through us. We plead on Christ's behalf, "Be reconciled to God."" –2 Corinthians 5:20

Because we are all on mission, Christians who don't live as ambassadors are still missionaries, they're just bad ones. Anyone who passively consumes culture is a bad missionary. Anyone who isolates himself from people who don't know Jesus is a bad missionary. Anyone who does not verbally proclaim the god news is a bad missionary. Anyone who walks in sin... well, you get the point.

For too long now, missionaries (in the traditional sense) have been telling missionaries (read: all Christians everywhere) that they aren't missionaries (in any sense). Is it any wonder, then, that many of us don't act like we're on mission?

Bridging the Divide

Over the last fifteen years or so, the word "mission" has been subject to multiple redefinitions. For a while, it was used almost exclusively to refer to the evangelization of the world. Then it was adopted (and slightly changed) by churches in the "missional movement," who were wrestling with what it means to be God's people in an increasingly non-"christian" culture.

Now, there's a bit of a stalemate between the international missions world, which tends to insist that mission should be narrowly defined within the parameters of global evangelism and church planting, and the missional movement, which makes a strong case that all of God's people are, in some sense, "sent" on God's mission.

For some time now, I've devoted lots of energy to finding people who are taking about mission and working to join that conversation. I've been pleased to find gracious hosts on either side of the "debate," and I've been pleased with the general desire on both sides to be faithful to Scripture. My hope is that this conversation would continue to move forward, and that, by God's grace, we may bridge the divide between "missions" and "missional."